This blog is part of a series related to Gov 1372: Political Psychology, a course at Harvard University taught by Professor Ryan D. Enos.

Would Harvard students in our class support in-party and out-party marriage? In this blog, I evaluate responses to a replication of the survey conducted in Klar et al. (2018) to evaluate affective polarization.

Background

The main finding from Klar et al. (2018) is that while some Americans are politically polarized, many simply don’t want to discuss politics. They show this through two national experiments asking about hypothetical in-party and out-party marriage of their children to someone who discusses politics either frequently or rarely. Their study also finds that strong partisans are more likely to be polarized and less supportive of out-party marriage overall than weak partisans. This makes sense give that strong partisans would likely have stronger beliefs and values that they are unwilling to compromise or sacrifice.

Harvard Responses

Professor Enos recreated the survey from Klar et al. (2018) using a sample frame of students in our Political Psychology course. Evaluating the findings, we find that the overall trends in the data are very similar to the ones found by Klar et al. (2018). The one difference in the Harvard sample data was a much higher proportion of students that were polarized and opposed to out-party marriage. However, this makes sense since the students in this class would be more political active and have more political opinions. Harvard students are by no means an accurate representation of US adults, so naturally the proportions would not be the same.

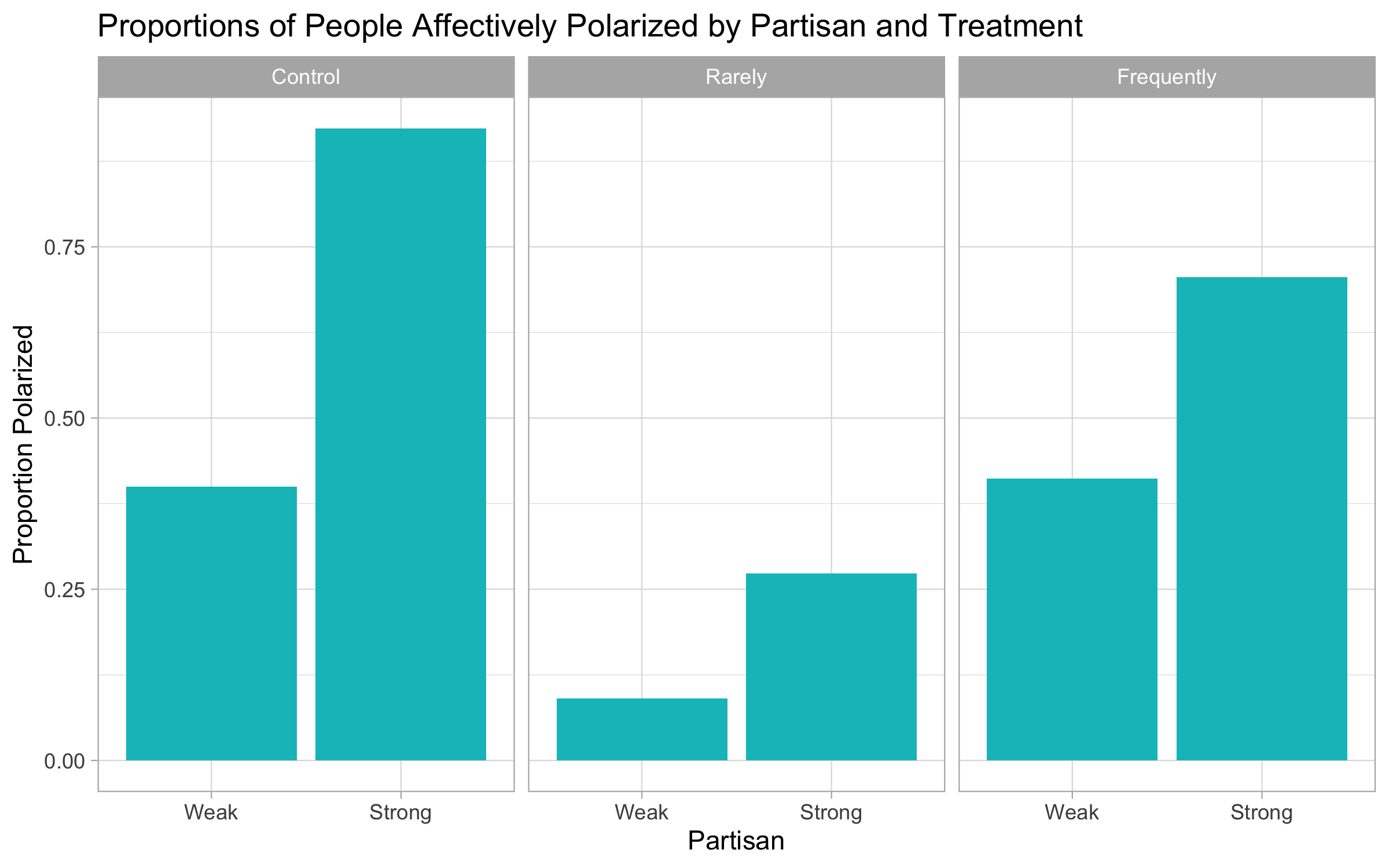

The first plot shows the proportion of respondents who were polarized depending on the treatment of whether the son- or daughter-in-law rarely discussed politics, frequently discussed politics, or a control in which neither was mentioned. The trend that mirrors the trend found by Klar et al. (2018) is that the treatment of rarely discussed politics resulted in the lowest proportion of respondents being polarized compared to the highest proportion of respondents being polarized when the treatment was frequently discussed politics.

However, when the respondents are also broken down by partisanship, we see that strong partisans are much more likely to be polarized than weak partisans. This makes sense because weak partisans should care less than strong partisans about in-party and out-party marriage since their opinions on politics are more muted than strong partisans.

Conclusion

It’s interesting to see that even when surveying Harvard undergraduates in a Government course, the same trends from Klar et al. (2018) appear. Given that Harvard tends to have more politically polarized students, these results conflict with what I might have expected from surveying Harvard undergraduates in a Government course. Klar et al. (2018) separated “a dislike for members of the other party with a dislike for partisanship in general” in their definition of affective polarization. This leads me to wonder if more Americans are polarized in that they dislike politicians of the other party more rather than all members of the other party. It would be interested to extend the research from Klar et al. (2018) to explore polarization of politicians rather than all party members.